TTP Podcast, Episode 30: The Electoral College – Protector of American Democracy?

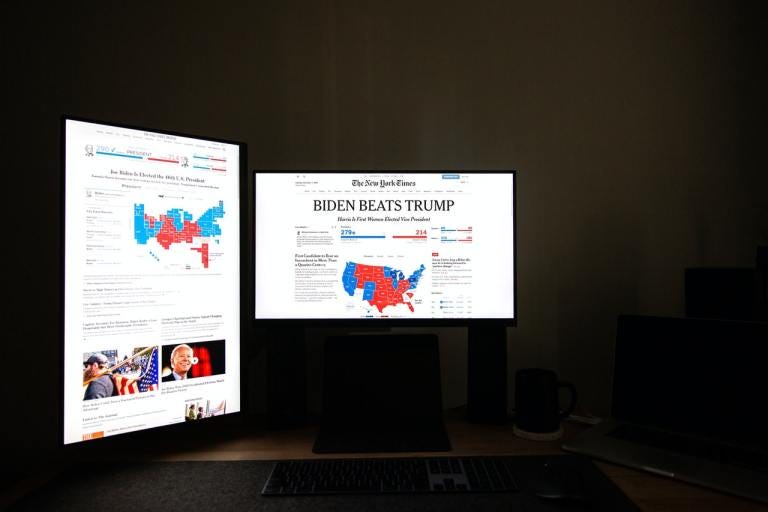

December 14 is the date that the Electoral College will cast its ballots for the United States President and it will likely be a victory for Joe Biden. President Trump continues with his slate of lawsuits alleging election fraud in numerous states, but said last week that he will concede only after he is officially defeated in the Electoral College. Is Trump’s refusal to concede sour grapes, or a very strict reading of the Constitution? It may be a little of both, but the winner of a Presidential election is not official until the Electoral College has cast its ballots and had them verified in Congress. It makes the process of electing the President longer and a little more complicated. Additionally, several past elections have seen candidates become presidents after losing the popular vote and winning the electoral vote. What gives? Is this undemocratic? Why does the US Constitution mandate such an odd intermediary step after a national vote? I’m going to address each of these questions in today’s podcast.

The Debate on the Electoral College

What the Constitution Says

The Electoral College is outlined in Article II, section I and amended by the 20th Amendment to include separate ballots for the VP.

Each party appoints slates of electors in each state, the candidate who wins the popular vote of that state gets to have their slate of electors cast their ballots on December 14 (the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December – since 1936) in their respective state capitols, those results are certified on January 6 by a joint session of Congress after the New Congress has been seated, with the duly elected President being inaugurated on two weeks later on January 20.

This system was established as a compromise between delegates at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 who wanted the people to elect the President and those who wanted Congress to appoint the President.

At issue in the Electoral College is what does representation mean? How is a general population to be represented justly?

The case for abolishing the Electoral College

In a November 15, 2020 editorial, the editors of WaPo made the following statement:

The electoral college, whatever virtues it may have had for the Founding Fathers, is no longer tenable for American democracy.

The abolishment of the Electoral College is not a new issue and has been frequently debated around election years. However, the 2000 and 2016 elections saw Republican candidates win office while losing the popular vote, thus ensuring that the abolishment of the Electoral College become a talking point primarily of Democrats and the political left in America. So, the quote above is nothing new, so much as an articulation of an increasingly mainstream argument. So what is that argument?

The argument to abolish the Electoral College is usually based on the following premises, which are all articulated in the Washington Post article.

The Electoral College forces candidates to spend time working to win votes in smaller, less populated states

Less populous states have more clout in this system, similar to how they have it in the Senate

The 50 states plus Washington DC and Puerto Rico all conduct their elections differently

Majority rule is normative for democratic elections

Acknowledged concerns with abolishing the Electoral College:

Difficulty of amending the Constitution

Increased regionalism

Greater extremism/polarization

National voting system

What is not acknowledged by the Washington Post editors:

Known effects of regionalism in other democracies (civil war)

The security problem of a national vote

Michael Uhlmann’s defense of the Electoral College

Who is Michael Uhlmann? He was a Senior Fellow and faculty member of the Claremont Institute, and visiting professor of political science at Claremont Graduate University who passed away in 2019.

According to Uhlmann, those unique elements that the Washington Post editors see as being problematic are features, not bugs of the American political system. That’s because we’re a federated republic, we’re not just one country. We’re 50 republics combined into one national entity.

Representation, therefore, means that a President can’t just represent the simple majority of the whole population, but the majority of states as well. So, the President has to campaign in different states, form his Cabinet from residentes of different states, etc.

Uhlmann’s argument is that if you change the mode of electing the president, you’re changing the character of the American political system. Ironically, he argues, choosing the president solely based on a national popular vote will make America less democratic not more, as presidential candidates craft less moderate messages, but instead develop platforms designed merely to capture populations centers.

Conversation starters

What areas of your life (work, school, family, etc.) operate purely on simple majority decision-making rules? How effective would you say that process is? Is its perceived effectiveness based on whether or not you land in the majority or minority? What do you see as some of the potential problems for majority-only decisions?

The spoken and written word (podcasts and reading)

Articles

Podcasts

TTP Podcast, Episode 19: “We the People” – Article I of the US Constitution

TTP Podcast, Episode 20: “The Buck Stops Here” – Article II of the US Constitution

TTP Podcast, Episode 21: The “Weakest” Branch? – Articles III-VII of the US Constitution

TTP Podcast, Episode 22: The Bill of Rights – Amendments 1-10

TTP Podcast, Episode 23: A More Perfect Union – Amendments 11-27

The last word

If elections were simply a matter of counting heads and stopping when you got to 50% plus one, we could dispense with all the checks and balances of the Constitution, including federalism, bicameralism, the separation of powers, and, yes, the Electoral College. The point of these time-honored devices, which are all part of an integral whole, is not to circumvent popular sentiment, but to shape and channel it in ways that support the principal end for which popular government is constituted: to secure the equal rights of all. Majority rule can become majority tyranny, as the wisest thinkers on politics have always known. The trick in establishing popular government is to empower the majority without endangering the rights of minorities.

Michael Uhlmann

The post TTP Podcast, Episode 30: The Electoral College – Protector of American Democracy? appeared first on Tim Talks Politics.